Single molecule studies of DNA repair

Background: DNA repair

DNA is damaged continuously by agents that occur naturally within our cells as well as by exogenous factors such as high-energy radiation or alkylating agents during chemotherapy. If unrepaired, the resulting DNA base modifications and strand breaks can lead to mutations in transcribed genes and tumour development as well as cell death. DNA repair is hence essential for the maintenance of genomic stability and cellular viability. Cells have developed a variety of DNA repair mechanisms, which are each specialised to target specific damages in the genetic code. We are interested in resolving and understanding the remarkably different strategies realised by different DNA repair systems to find and recognise their target sites in DNA, and in the intricate interplay between different repair systems. Specifically, we currently work on damage recognition in base excision repair (BER), nucleotide excision repair (NER), and by the direct damage reversal DNA alkyltransferase (AGT).

Methods:

Single molecule imaging by Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) enables us to directly visualize and structurally characterize protein- and protein-DNA complexes at the level of the individual molecules. In addition, we use single molecule fluorescence microscopy coupled with an optical tweezers system to investigate dynamic processes on DNA in DNA lesion search and recognition. We further complement these studies with biochemical and biophysical ensemble techniques to address functional properties of the involved interactions.

Research foci:

1. Mechanical sensing in DNA lesion search and recognition by BER glycosylases.

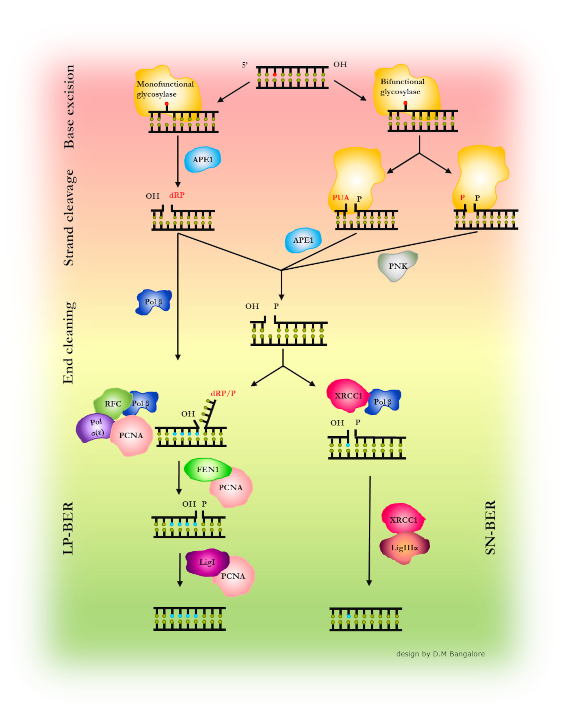

Subtle chemical alterations of DNA bases such as oxidation or alkylation can cause transition mutations in the DNA and thus lead to genetic instability. These lesions are typically targeted and repaired by the base excision repair (BER) (Figure 1).

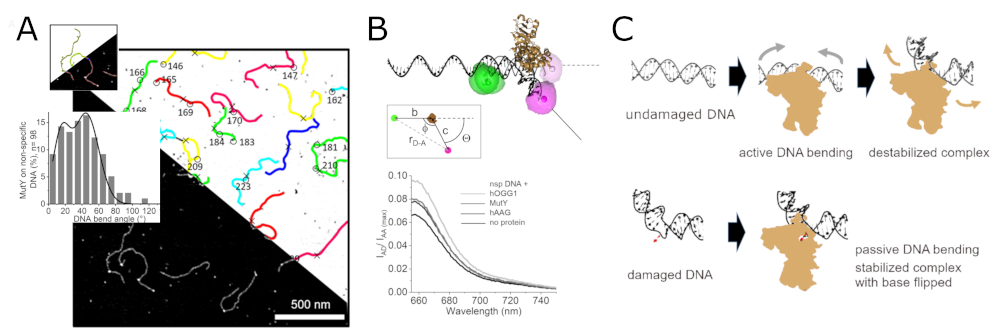

Glycosylases, the initiating enzymes of BER, employ a base flipping mechanism to identify their target inside a catalytic pocket. The specific approach for recognition of DNA flaws and damages, however, differs subtly between different glycosylases. There are a number of different glycosylases, 11 in humans, that each recognize and repair only one or only a few types of chemical base modifications. To enhance the efficiency of the lesion search process, glycosylases seem to exploit the mechanical properties at their specific target lesions in an initial lesion sensing step (Figure 2). [1,2]

2. Transcription regulation by the BER glycosylase hOGG1

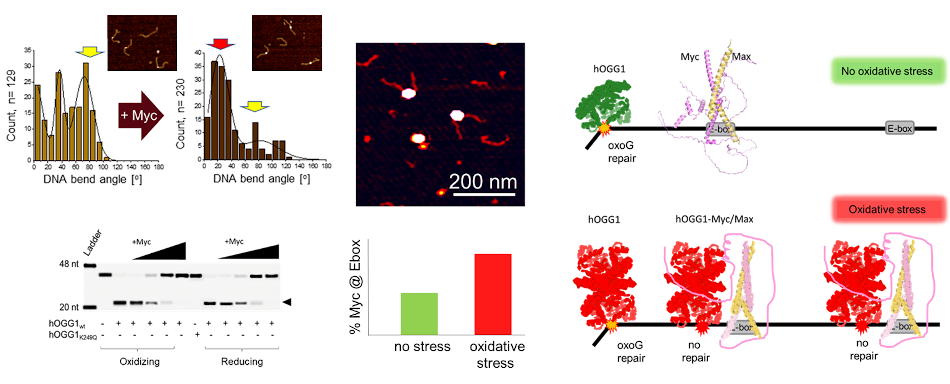

Interestingly, the BER glycosylase hOGG1 (human oxoguanine glycosylase 1) has also been observed to function in the regulation of gene transcription under oxidative stress, in addition to its generic function in the repair of oxidative (oxoguanine) DNA lesions. We were recently able to resolve the molecular mechanism of recruitment of the oncogene transcription factor Myc by hOGG1. Using AFM in combination with biochemical approaches, we showed oxidation induced dimerization of hOGG1, enhanced interactions of the oxidized hOGG1 dimer with Myc (compared to monomeric hOGG1 under reducing conditions), inactivation of hOGG1 catalytic activity by Myc, and enhanced recruitment of Myc/Max to its E-box recognition sequence in proximity to oxidative lesions in DNA by hOGG1 specifically under oxidative stress conditions (Figure 3). [3]

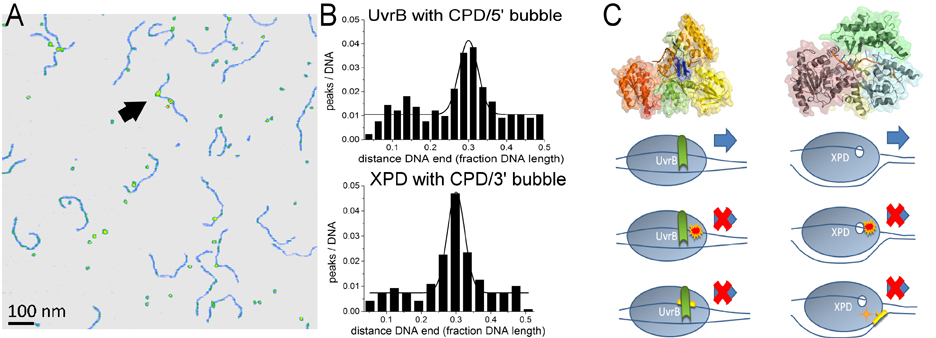

3. Conservation and divergence in NER lesion recognition.

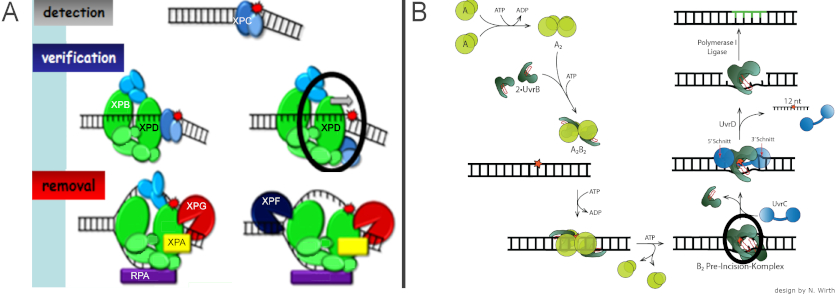

In the highly conserved mechanism of NER, which targets a multitude of different DNA damages including UV irradiation damages, DNA target site recognition involves ATPases/helicases. In general, prokaryotic and eukaryotic nucleotide excision repair (NER) share the same mechanistic approach of excising an oligonucleotide containing the lesion from the DNA (Figure 4) [4-6]. They also display largely comparable target lesion specificities and repair efficiencies. However, to achieve the recognition and identification of their specific target lesions, eukaryotic and prokaryotic NER systems employ subtly different molecular approaches (Figure 5). [4,5]

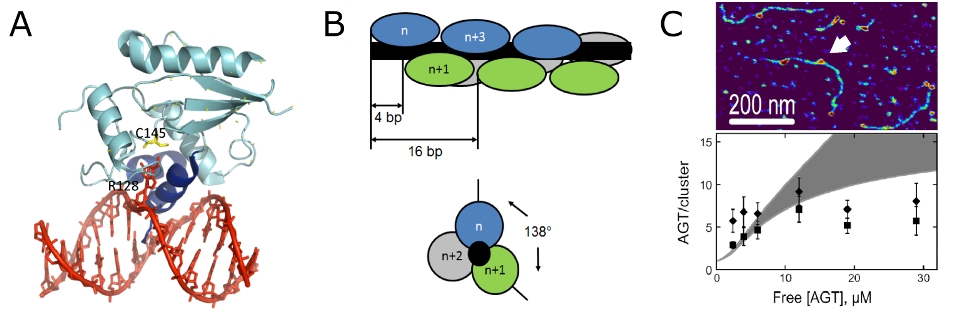

4. Cooperative clusters in lesion search by the O6 alkylguanine DNA alkyltransferase AGT

The human O6-alkylguanine DNA alkyltransferase, AGT, recognizes and removes highly mutagenic and cytotoxic

alkylation damages in our genetic material. AGT has also recently received particular interest as an inhibitor target

to support chemotherapeutical efficiency, because AGT repair activity interferes with alkylation damage that is deliberately

introduced into DNA to kill cancer cells.

Direct damage reversal by AGT involves search, recognition, identification, and removal of the alkyl lesion, which are all

performed by the same protein and leave the DNA completely intact with the offending chemical group transferred to the protein.

Using a combination of AFM imaging and analytical ultracentrifugation (AUC), we were able to confirm an atypical form of

cooperative non-specific DNA binding, in which AGT forms protein clusters with a short, limiting length on DNA (Figure 6). [7-9]

These short length AGT clusters have been proposed to serve to enhance the speed and efficiency of DNA lesion search by AGT using

a mechanism of facilitated diffusion based on preferential monomer addition at the 5’ end and dissociation from the 3’ end of clusters.

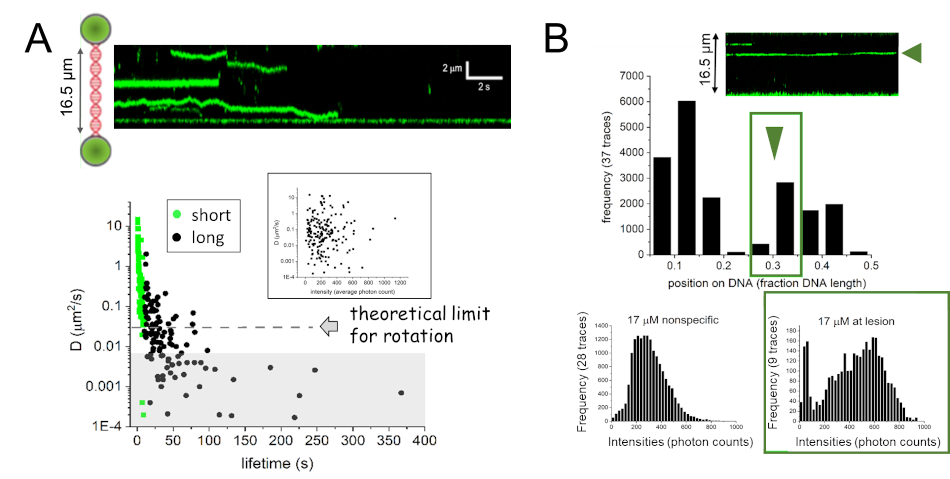

Interestingly, however, single molecule fluorescence microscopy coupled with a dual trap optical tweezers system has shown rotational

movement of AGT on DNA, but no enhancement of DNA translocation for AGT clusters compared to monomeric complexes (Figure 7A). Instead,

these studies revealed preferential stabilization of clusters at an alkyl lesion in DNA, indicating a role of AGT clusters in lesion

processing (Figure 7B). [10]

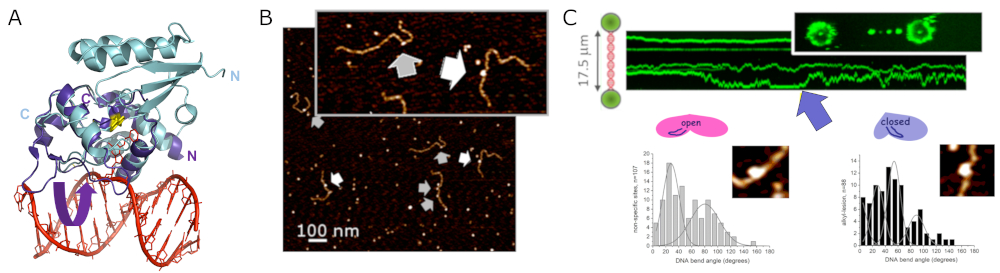

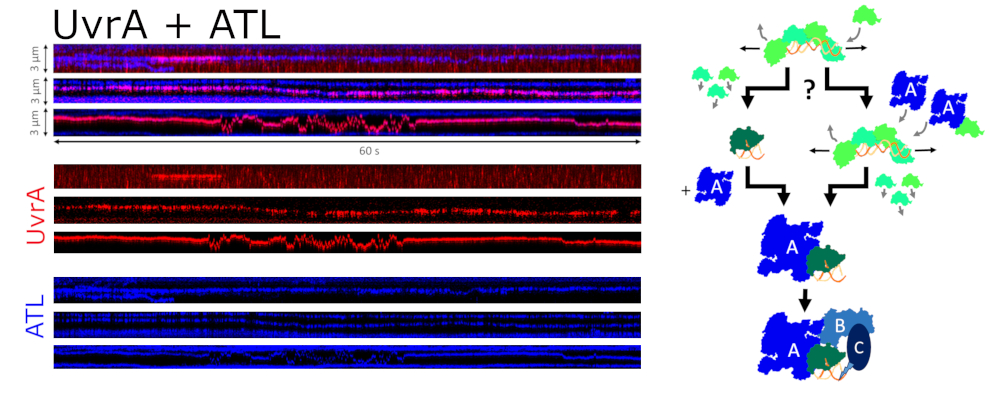

4. The link between alkyl lesion repair and the NER system by the alkyltransferase-like ATL protein

Alkyltransferase-like proteins (ATLs) form a protein family with high structural similarity to AGTs (Figure 8A). Single molecule AFM and fluorescence optical tweezers data show highly specific recognition of alkylguanine lesions in DNA and rapid scanning of the DNA by ATL in search of these target lesions (Figure 8). Like its alkyl lesion repair active homolog AGT, ATL forms clusters on DNA at high protein concentrations, which scan the DNA for lesions. While ATL itself is unable to process alkyl lesions, it recruits UvrA, the initiating enzyme of prokaryotic NER, to these lesions. ATL thus initiates NER of alkylguanine lesions that are otherwise not (or only poorly) recognized by the NER system (Figure 9). [11]

5. The beauty of AFM and combination with Fluorescence Microscopy

AFM is highly synergistic to other structural techniques such as X-ray crystallography and kinetic studies of DNA repair processes. It is the only

imaging platform, which allows the monitoring of protein dynamics without any labeling modification in physiologically relevant conditions. In

contrast to crystallography, it does not require homogeneity of the sample molecules allowing it to resolve structural and stoichiometric heterogeneity

in a sample. Conformational heterogeneity can, for instance, be an important indicator of intra- or inter-molecular flexibility. Importantly, AFM is one

of very few techniques that allows the resolution and structural characterization of non-specifically bound protein-DNA complexes (e.g. DNA lesion search

complexes). Although AFM does not achieve the high atomic resolution of crystallography, its spatial resolution at the molecular or sub-molecular level

can nevertheless often resolve individual protein domains and provide valuable structural information on proteins and protein complexes. [12-14]

AFM topographic images contain 3D information. We can hence measure the volumes of sample particles in the images to estimate their molecular masses and,

for instance, distinguish between different oligomeric states of a protein. [12-14]

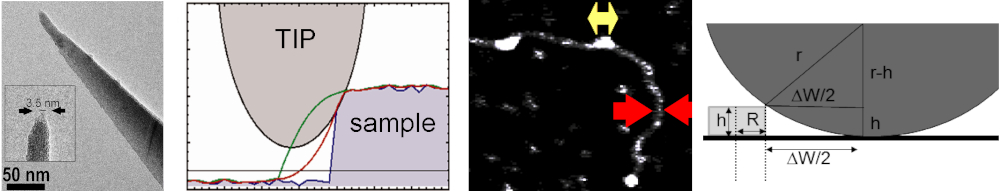

It is important to bear in mind that AFM images constitute convolution images of the true sample topography and the AFM tip geometry. The contribution of

the AFM tip to image features can, however, be calculated and subtracted post-experimentally when the approximate end diameter of the AFM tip is known.

Using simple geometrical models to describe sample particles and AFM tip, we can extract the AFM tip dimensions from convoluted AFM images using DNA as

a standard (Figure 10). The tip contribution to other sample particles can then be calculated and subtracted. [7,15]

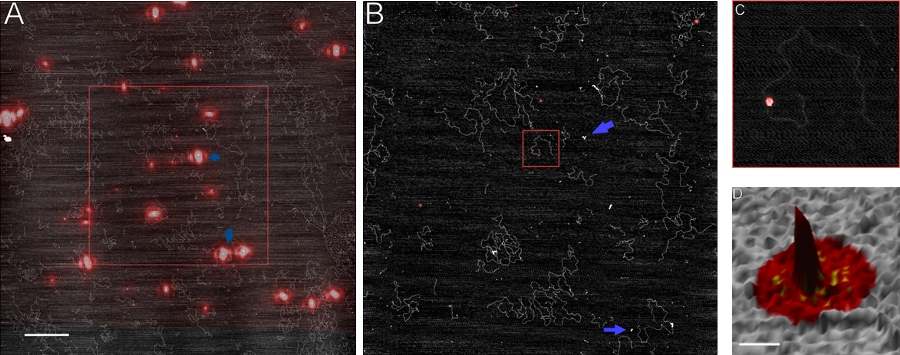

AFM can also be combined with other techniques to provide orthogonal information on protein-protein and protein-DNA interactions. Combining AFM with

super-resolution fluorescence microscopy (FIONA, fluorescence imaging with one nanometer accuracy) opens the possibility of pinpointing specific,

fluorescently labeled proteins within heteromeric assemblies on DNA (Figure 11) [16].

References

[1] DM Bangalore, HS Heil, CF Mehringer, L Hirsch, K Hemmen, KG Heinze, I Tessmer (2020) Automated AFM analysis of DNA bending reveals initial lesion sensing strategies of DNA glycosylases, Scientific Reports 10(1), 15484l, doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-72102-7.

[2] CN Buechner, A Maiti, AC Drohat, I Tessmer (2015) Lesion search and recognition by thymine DNA glycosylase revealed by single molecule imaging, Nucleic Acids Research 43(5): 2716-2729, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv139.

[3] DM Bangalore and I Tessmer (2022) Direct hOGG1-Myc interactions inhibit hOGG1 catalytic activity and recruit Myc to its promoters under oxidative stress, Nucleic Acids Research 50(18): 10385-10398, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac796.

[4] J Gross, N Wirth, I Tessmer (2017) Atomic force microscopy investigations of DNA lesion recognition in nucleotide excision repair, Journal of Visualized Experiments (123), e55501, doi: 10.3791/55501.

[5] N Wirth, J Gross, HM Roth, CN Buechner, C Kisker, I Tessmer (2016) Conservation and divergence in nucleotide excision repair lesion recognition, Journal of Biological Chemistry 291(36): 18932-18946, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.739425.

[6] CN Buechner, K Heil, G Michels, T Carell, C Kisker, I Tessmer (2014) Strand specific recognition of DNA damages by XPD provides insights into Nucleotide Excision Repair substrate versatility, Journal of Biological Chemistry 289(6): 3613-3624, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.523001.

[7] I Tessmer* **, M Melikishvili**, MG Fried*(2012) Cooperative cluster formation, DNA bending and base-flipping by O6-alkylguanine DNA alkyltransferase, Nucleic Acids Research 40(17): 8296-8308, doi: 10.1093/nar/gks574. (*joint correspondence, **equal contributions)

[8] I Tessmer* and MG Fried* (2015) Characterization of homogeneous, cooperative protein-DNA clusters by sedimentation equilibrium analytical ultracentrifugation and atomic force microscopy, in: Methods in Enzymology 562 “Analytical Ultracentrifugation” (ed. J Cole): 331-348, doi: 10.1016/bs.mie.2015.06.036. (*joint correspondence)

[9] I Tessmer* and MG Fried* (2014) Insight into the cooperative DNA binding of the O6-alkylguanine DNA alkyltransferase, special issue on “Single molecule approaches: watching DNA repair one molecule at a time”, DNA Repair 20: 14-22, doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2014.01.006. (*joint correspondence)

[10] N Rill, A Mukhortava, S Lorenz, I Tessmer (2020) Alkyltransferase-like protein clusters scan DNA rapidly over long distances and recruit NER to alkyl-DNA lesions, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA 117(17): 9318-9328, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1916860117.

[11] S Kono, A van den Berg, M Simonetta, A Mukhortava, EF Garman, I Tessmer (2022) Resolving the subtle details of human DNA alkyltransferase lesion search and repair mechanism by single-molecule studies, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA 119(11): e2116218119, doi: 10.1073/pnas.2116218119.

[12] CN Buechner and I Tessmer (2013) DNA substrate preparation for atomic force microscopy studies of protein-DNA interactions, Journal of Molecular Recognition 12: 605-17, doi: 10.1002/jmr.2311.

[13] DM Bangalore and I Tessmer (2018) Unique insight into protein-DNA interactions from single molecule atomic force microscopy, AIMS Biophysics 5(3):194-216, doi: 10.3934/biophy.2018.3.194.

[14] I Tessmer*, P Kaur, J Lin, H Wang (2013) Investigating bioconjugation by atomic force microscopy, Journal of Nanobiotechnology 11:25. doi: 10.1186/1477-3155-11-25. (* correspondence)

[15] AT Winzer, C Kraft, S Bhushan, V Stepanenko, I Tessmer (2012) Correcting for AFM tip induced topography convolutions in protein-DNA samples, Ultramicroscopy 121: 8-15, doi: 10.1016/j.ultramic.2012.07.002.

[16] DN Fronczek, C Quammen, H Wang, C Kisker, R Superfine, R Taylor, DA Erie, I Tessmer (2011) High accuracy FIONA-AFM hybrid imaging, Ultramicroscopy 111: 350-355, doi: 10.1016/j.ultramic.2011.01.020.